ACER RECOGNIZES BLACK HISTORY MONTH

- ACER

- Feb 1, 2022

- 1 min read

Updated: Jul 28, 2022

This month is an opportunity to recognize the people and events that have shaped African Diaspora history in America.

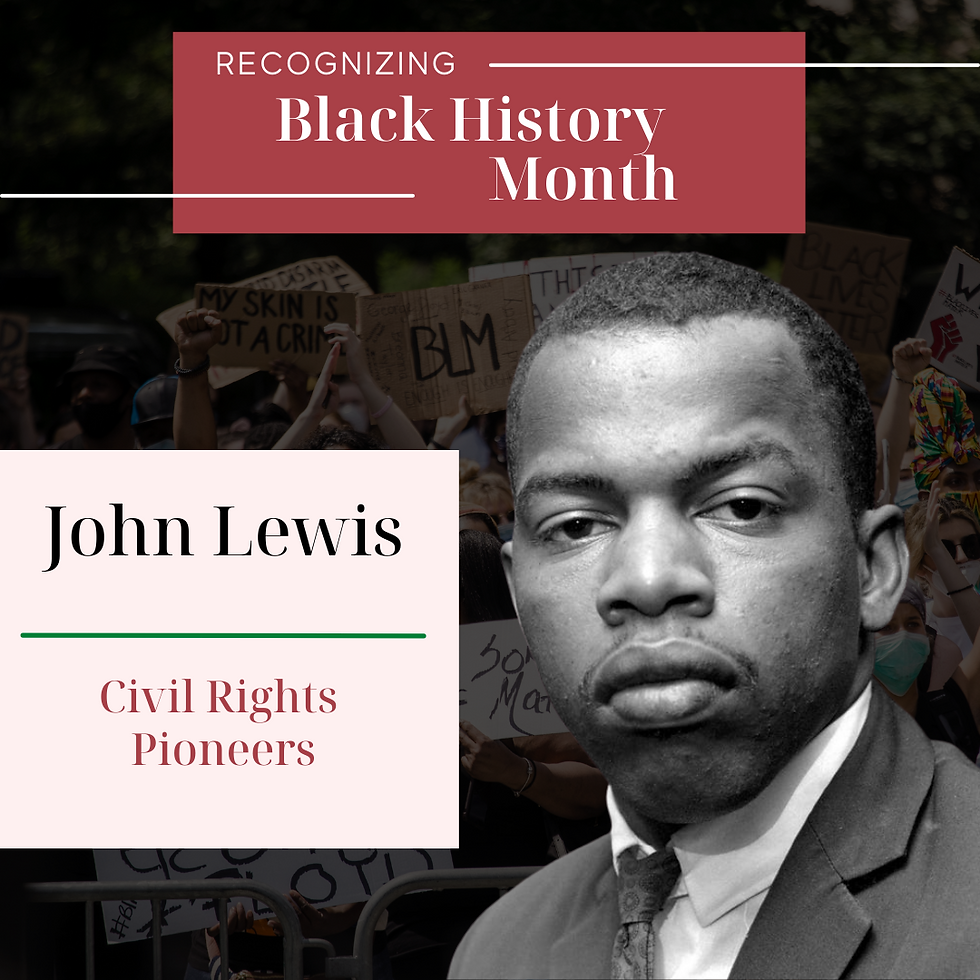

BLACK CIVIL RIGHTS ADVOCATES

|  |  |

The late John Lewis was one of the “Big Six” Civil Rights leaders. Lewis participated in 100s of demonstrations, being arrested over 40 times. While Chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee Lewis organized the 1963 March on Washington. The passing of the 1964 Civil Rights Act did not lead to increased voting rights for African-Americans, so in 1965 Lewis led a march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama to demand further action on civil rights. The march, known as “Bloody Sunday,” was met with brutal police violence against the protesters. However, the protest was successful in pressuring Congress to pass the Voting Rights Act that same year. Lewis continued his work, serving in the U.S. House of Representatives until his death in 2020. | Shirley Chisholm is best known for making history as the first black woman to campaign for the Democratic Party presidential nomination, but she has had many other accomplishments throughout her life. She started her political career in 1953 when she campaigned for Brooklyn’s first Black judge. This experience led her to pursue politics. In 1964 Chisholm went on to successfully run for the New York State Assembly where she served from 1965 to 1968, accomplishing many feats such as granting domestic workers unemployment benefits. Then in 1968 Chisholm became the first African-American woman elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. Chisholm continued her work including in her run for president where she brought racial and gender equity issues to the national stage. | In 1957 a group of black students known as the “Little Rock Nine” enrolled at the formerly all-white Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, testing the principle of equitable education established by Brown V. Broad of Education. On the first day of school, the students, Minnijean Brown, Elizabeth Eckford, Ernest Green, Thelma Mothershed, Melba Patillo, Gloria Ray, Terrence Roberts, Jefferson Thomas, and Carlotta Walls, were blocked from entering by the Arkansas National Guard. That same month, President Eisenhower sent in federal troops to escort the students to school. The students, who were recruited by the NAACP because of their strength and determination, received training on how to deal with racist hostility. As the Little Rock Nine endured angry racist mobs, they paved the way for many more people to stand up to segregation. |

BLACK HOUSING ADVOCATES

|  |  |

Dorothy Mae Richardson was a housing activist in Pittsburgh. Recognizing the need for affordable and safe housing, Dorothy created the Citizens Against Slum Housing (CASH) group which pressured landlords to fix and maintain housing. The CASH group, composed mostly of black women, created Neighborhood Housing Services (NHS) to combat the redlining of black residents. The NHS group secured more than one million dollars from private financers for housing repairs and homeownership. Dorothy’s community model inspired over 300 similar programs in cities across America. The NHS group’s work led to the government formally creating NeighborWorks America, a congressional chartered nonprofit organization based on Dorothy’s work. Learn More | The late Mel Reeves was a housing rights advocate based in Minnesota. After the 2008 housing crisis that led to thousands of Minnesotans losing their homes, Mel Reeves contributed to various housing causes. Including the Occupy Our Homes National Day of Action in 2012 which drew attention to empty homes in Minnesota as well as the need to shelter people. Additionally, in 2013 Mel and other community activists followed in the footsteps of the Freedom Riders by riding on a yellow school bus across Minnesota to bring attention to the foreclosure housing crisis. Until his death in 2022, Mel continued to write as a journalist and advocate for racial and economic equity. Listen to Mel in his own words here. | Joseph Lee Jones, a black man, and his wife Barbara Jo Jones, a white woman, sued the Alfred H. Mayer Co., one of Missouri’s biggest homebuilders, after the company refused to build them a home because of Joseph’s race. The couple took their case to the Greater St. Louis Committee for Freedom of Residence, a group that advanced racial integration in housing. Samuel Liberman, lawyer and chairmen of the Committee, filed their suit in federal court. In a 7-2 decision, the Supreme Court ruled that companies could not refuse to sell a home because of a buyer’s race. Unfortunately, the Joneses did not get to purchase their dream home, but their case set a standard for justice that still stands today. |

BLACK ENTREPRENEURSHIP

|  |  |

Sarah Breedlove—later known as “Madame C.J. Walker”—was born in 1867 on a Louisiana plantation to enslaved parents. Despite growing up as an uneducated sharecropper, Ms. Walker became one of the most successful entrepreneurs of the 20th century. In 1905 Ms. Walker started her own business selling “Madam Walker’s Wonderful Hair Grower.” For years Walker promoted her products, traveling throughout the south selling her products door-to-door, in churches and in salons. As her business skyrocketed, Walker used her wealth for social good; in 1916, while living in New York, Walker helped finance the NAACP’s anti-lynching movement. Madame C.J. Walker died a millionaire who financed many social causes. | Harry Pace was an insurance executive and the founder of Black Swan Records, the first widely distributed African-American-owned record label. The record company, which started in Pace’s basement, opened the door for thousands of black musicians who went on to have successful careers. Later on, Mr. Pace opened the Northeastern Life Insurance Company which became one of the largest black-owned businesses in the north. Mr. Pace’s fascinating life story, including his attempt to pass as white, is detailed on Radiolab’s podcast. | “Black Wall Street” was an affluent Black community in the Greenwood District of Tulsa, Oklahoma. It served as an example of the burgeoning entrepreneurship of Black Americans in the 20th Century. While today Black Wall Street is remembered for the white supremacist riot that killed 300 people, destroyed 1,200 homes and 190 businesses, the people of Black Wall Street should be remembered for how quickly they rebuilt their neighborhood. “They just were not going to be kept down. They were determined not to give up,” recalled Eunice Jackson, a survivor of the massacre. Despite white authorities doing everything in their power to prevent the residents from rebuilding, residents defiantly rebuilt many of their homes and businesses, sometimes under the cover of night to avoid authorities. Today we honor their determination and resilience. |

HEALTH EQUITY

|  |  |

Dr. Charles Drew was an African American surgeon whose pioneering work in blood transfusion has saved many lives. Known as “the father of blood banking,” Dr. Drew developed a way to separate blood from plasma, allowing it to be stored for a week. During WWII, Dr. Drew organized blood drives at New York City hospitals. The program, called “Blood for Britain,” lasted five months, with 15,000 American blood donors participating. The American Red Cross noticed his work and Dr. Drew was appointed director of the American Red Cross’ first blood bank in 1941, which oversaw blood for use by the U.S. Army and Navy. Later, Dr. Drew took a moral stand against the American Red Cross’ racist and unscientific practice of segregating blood donations by race—the policy was reversed in 1950. Throughout his life, Dr. Drew remained dedicated to not only science and medicines but also racial equity. | Patricia Bath was an ophthalmologist best known for her invention of laserphaco—a surgical tool that uses a laser to vaporize cataracts, a leading cause of blindness. After receiving her medical degree in 1968, Dr. Bath interned at Harlem Hospital where she conducted a study that concluded that blindness among African Americans was nearly double the rate of blindness among white Americans. To combat this health disparity, Dr. Bath developed “Community Ophthalmology,” a discipline now studied and practiced worldwide which utilizes methods of public health, community medicine, and ophthalmology. She also introduced eye surgery services to Harlem Hospital, treating thousands of mostly black patients. Dr. Bath was a life-long advocate for patient rights and blindness prevention and treatment until her death in 2019. | When it comes to tackling the disparities in healthcare we have many dedicated black doctors, nurses, and healthcare workers to thank for their work in providing vital medical care to the black community. We would like to thank the black healthcare workers who support our vaccine clinics and helped vaccinate many of our community members. Without them, we would not be able to do the critical work of protecting our communities. |

Comments